Bodily Integrity

Why we shouldn't chip away at ourselves.

I recently came across this brilliant piece by father_karine assailing the modern beauty-industrial complex. As father_karine notes, it is becoming normal for young women to inject, chisel, and otherwise modify their bodies in service of an imagined ideal. This trend has caused many a beautiful woman to discard her unique features to embrace a look of manufactured sameness. father_karine argues:

I believe one of the biggest existential threats to modern women is the beauty-industrial complex, that is the vast network of corporations that manufactures and sells us an endless slew of products, services, images and ideologies intended to destroy our self-worth for the benefit of shareholders.

father_karine recognizes that much of this “beauty-industrial complex” and its power emanate from spiritual malaise:

Yeats warned of the dangers of the Industrial Revolution and withdrew into his mythologies. Bartky wrote of consumerism displacing the family and religion as the chief behavioral regulator in our society.

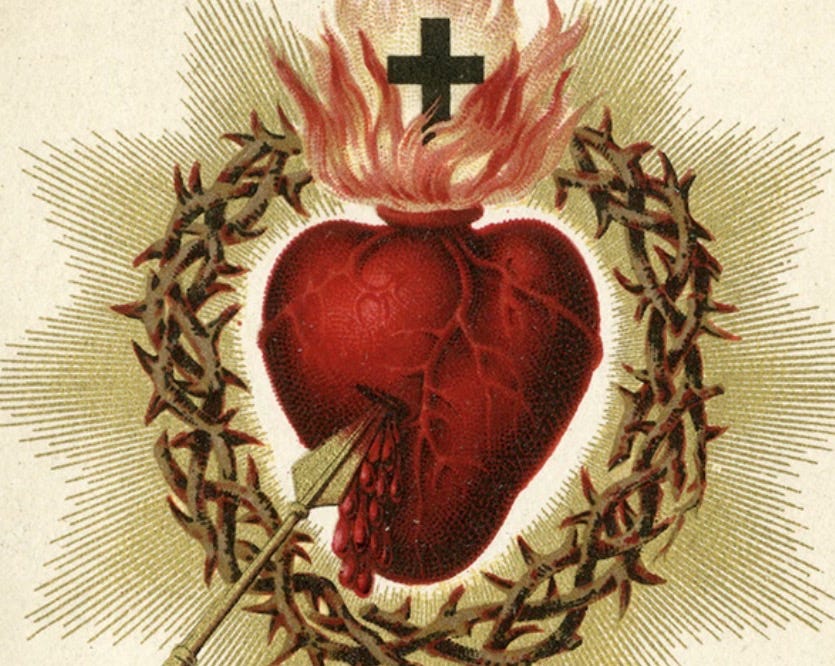

I think there is more to the problem than this, though. The beauty-industrial complex is a symptom of the spiritual crisis overwhelming the industrialized West, at once a result and a progenitor of the scourge of internet pornography, TikTok, and related media that encourage women to mold their bodies into inhuman facsimiles.

The crux of this spiritual problem is that, as Pope Benedict XVI observed in his encyclical Caritas in Veritate, “modern man is wrongly convinced that he is the sole author of himself, his life and society.” In fact, “[t]he human being is made for gift, which expresses and makes present his transcendent dimension.”1

Our body is a gift we receive and it is a gift we give to others, to those we love. This is most palpably true of women who have biological children, who provide their bodies as their children’s first shelter against the world, but it is true of everyone. The man who shovels an elderly neighbor’s driveway is using his body as a gift to another, as is the religious sister who makes a meal for the homeless.

Postmodern culture focuses on what we can gain from using our bodies - pleasure, self-actualization, social capital. This is backwards. Our body is ours to cherish and for those we love to cherish. To carve away features our culture deems “objectionable” is a rejection of our own transcendence, and also of the people who created us.

The protagonist of C.S. Lewis’s novel Til We Have Faces is an ugly woman named Orual who wears a permanent veil to conceal her appearance. She says of the veil: “It is a sort of treaty made with my ugliness.”2

While Lewis died before the advent of the modern medspa, Orual’s veil serves as a metaphor for all the barriers we place between our faces and the world, and it demonstrates the problems with plastic surgery. Orual’s veil represents the tools, such as Botox and body sculpting, that we use to hide our vulnerabilities.

The veil also represents the separation between our world and the next, meaning the difference between how the world sees us and how God sees us.

The beauty-industrial complex specializes in generating the more modern version of Orual’s veil, a barrier intended to conceal the human frailty. Plastic surgery asks people to look but prohibits them from seeing us. I think this is why the features produced by common surgeries intuitively repulse many people. We know we are witnessing a paradox, an attempt to mend imperfection that only makes our own frailty more apparent.

Til We Have Faces is a story about gods and mortals. At one point, Orual’s sister Psyche, who is married to the god Cupid of Roman mythology, says she is “[a]shamed of looking like a mortal -- of being a mortal” before her divine husband. When Orual asks Psyche how she could help being human, Psyche responds: “Don’t you think the things people are most ashamed of are things they can’t help?”

Orual concludes, “I thought of my ugliness and said nothing.”3

This is the problem the beauty-industrial complex tells us it is fixing - the things we can’t help. The beauty-industrial complex tells us we can paper over our flaws and somehow separate ourselves from the world of mortals, the quotidian processes of aging and death. It tells us we can face others without ever showing them who we really are.

These body modifications call to mind the story of Adam and Eve hiding their nakedness in the Garden of Eden, even though God can see everything.4 It’s the same doomed urge driving the old to look young through cosmetic surgery, as if they can outwit their own mortality.

In her beloved book Little Women, Louisa May Alcott offers a simple but compelling truth - “love is a great beautifier.”5 Alcott is right - the glow of love enhances our features in ways nothing else can. And nobody can buy love. Love, like death, is an equalizer.

Since real love is not a commodity, the corporate interests ruling our culture undermine and reject it. We have lived for decades under a technocratic paradigm that promised to liberate us from the shackles of our imperfect bodies, including homely features, signs of aging, and even natural fertility. As Wendell Berry has observed, this bid for freedom has not only alienated us from our bodies, but removed any possibility of finding meaning in them.6

The beauty-industrial complex is fueled by our desperation for love, which is the very thing it can never give us. Cosmetic procedures also speak to our fear of death and aging, and the ways in which we deceive ourselves about them.

How does one solve these problems?

Accept that you are not perfect. Accept that you will die. Above all, accept, as Pope Benedict XVI once said, “Each of us is willed. Each of us is loved. Each of us is necessary.”7

Pope Benedict XVI, Encyclical Letter: Caritas in Veritate, Chapter Three. The Holy See, 2009 (https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xvi_enc_20090629_caritas-in-veritate.html).

C.S. Lewis, Til We Have Faces, (1956) (republished by HarperOne in 2017), Chapter Sixteen.

Id. at Chapter Ten.

Genesis 3:4 - 13, RSVCE.

Louisa May Alcott, Little Women, Part Two, Chapter 24 (1868) (republished in 2008 by Puffin Books).

Wendell Berry, “Rugged Individualism,” The World Ending Fire (ed. Paul Kingsnorth), 2017, originally published 2004 (“this too is tragic, for it sets us ‘free’ from responsibility and thus from the possibility of meaning.”)

Homily of Pope Benedict XVI, 24 April 2005, The Holy See (https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/homilies/2005/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20050424_inizio-pontificato.html).

"Our body is a gift we receive and it is a gift we give to others, to those we love."

Kelly, your writing lately has been so perfectly timed for me. I'm nowhere near injections and scalpels, but I have a daughter aging into those particularly fragile years, and I'm about to deliver my fifth son whom I want to raise into an honorable man with his brothers, and oh yeah my own body is a certain way as a result of all of these things. So many wrestlings over here and it's a blessing to know women can think through these issues together even if we are in different places. Thanks for writing so clearly and beautifully, as always.

Lovely piece. I’ve thought of that Little Women quite so often since I first read it as a single woman; it has stayed with me. And the idea of Orual’s veil being able to serve as a metaphor for the modifications we make to ourself is fascinating