Despair is en vogue. I recently navigated to the front page of Reddit by mistake and saw a tweet that said (paraphrased): “nobody under forty expects anything good to happen ever again.”

I once found these sentiments annoying. Now they make me angry.

I have dabbled in despair. From my twenty-seventh birthday to my thirtieth this month, I have experienced four miscarriages along with the greatest blessing of my life, the birth of my son. Sometimes the pathos of it all is overwhelming. Like many young people, I never thought anything really bad would happen to me. I thought I was meant to be anxious about minor problems forever.

My point is that I understand the allure of the abyss. But we need to be serious. One of the worst parts of internet culture is the constant encouragement to feel sorry for oneself.

The internet is dangerous because it fuels our worst impulses. If you’re having a bad day, it can feel comforting to come across a tweet like the one I described above. But if you see the same idea flicker past for three hours a day while you scroll on Reels, you will eventually believe that nothing good will ever happen to you again. You will feel angry and think your anger is justified. You will find someone else to blame.

That is a road that leads nowhere.

I was reflecting on all of this recently when I came across a prescient essay1 by

, in which she recommended Joan Didion’s “On Self-Respect.”2 It’s very short - you should read it. But I’ll distill the best points here.Didion argues that self-respect means accepting responsibility for one’s own life, which entails the realization that the world owes us very little. She observes that to earlier generations, “it did not seem unjust that the way to free land in California involved death and difficulty and dirt.”3

According to Didion, a lack self-respect “is to be locked into oneself, paradoxically incapable of either love or indifference.”4

Didion is right. We must accept ourselves, but not in the way influencers tell us. We have to accept that our judgment is not always good, that we are not always right, that we have all been unfair to others.

This is why self-acceptance requires humility.

To be humble you must see yourself clearly. This is not fun, and I don’t think anyone ever masters it. You have to work on assessing yourself in an honest way throughout your life. But this is also why loss can be a gift. Loss forces us to reconcile with the least lovable version of ourselves. This reconciliation can help us accept our deep flaws, our lack of merit, our sheer dependence on others. This is how you come to see yourself clearly.

Humility is little valued in our culture. Being right - or at least having a large number of people believe you are right - is the epitome of modern virtue. But in the grand scheme of things, being right is worth little. What matters is whether you admit when you are wrong.

Self-respect and humility are my first two practical alternatives to despair. The last and most important one is faith.

Few people understood the temptation to despair better than Fyodor Dostoevsky, who was arrested and sentenced to death at twenty-seven for joining a socialist literary society. Dostoevsky was marched to a firing squad before the Tsar commuted his sentence at the last second. The Tsar sentenced him to four years of hard labor and six years of Siberian exile instead.5

Dostoevsky only returned home after nearly eleven years in Siberia. He married, only to lose his first child when she was three months old. He had three more children, one of whom died at age three.6 Dostoevsky’s life was marred by tragedy after tragedy, but he never despaired. Instead he wrote some of the greatest literature of all time.

Dostoevsky did explore despair a great deal, though, and never more so than when he invented the cynical atheist Ivan Karamazov.

Ivan does not believe in God because he does not believe that an all-knowing, all-loving, all-powerful God could allow evil.7 However, Ivan also argues - first sarcastically and then with increasing anxiety - that objective morality is not possible without God. Dostoevsky writes:8

Were mankind’s belief in its immortality to be destroyed, not only love but also any living power to continue the world would at once dry up in it. Not only that, but then nothing would be immoral any longer, everything would be permitted…Evildoing should not only be permitted but should even be acknowledged as the most necessary and the most intelligent solution for the godless person!

Another atheist in The Brothers Karamazov insists that people can govern themselves based on ethical principles such as the famous “liberty, fraternity, and equality” of the French Revolution.9 But such principles prove insufficient in the face of a moral crisis, and Ivan goes insane.

Dostoevsky likely based Ivan in part on himself prior to his imprisonment. Dostoevsky realized in Siberia that secular ethics are not enough. This is why he wrote: “It’s impossible for a convict to be without God, even more impossible than for a non-convict!”10 On his deathbed, Dostoevsky told his surviving children: “Have absolute faith in God and never despair of His pardon.”11

Dostoevsky learned in the valley of the shadow of death that despair is a dead end. Despair can only generate more despair. Faith is the only way to survive.

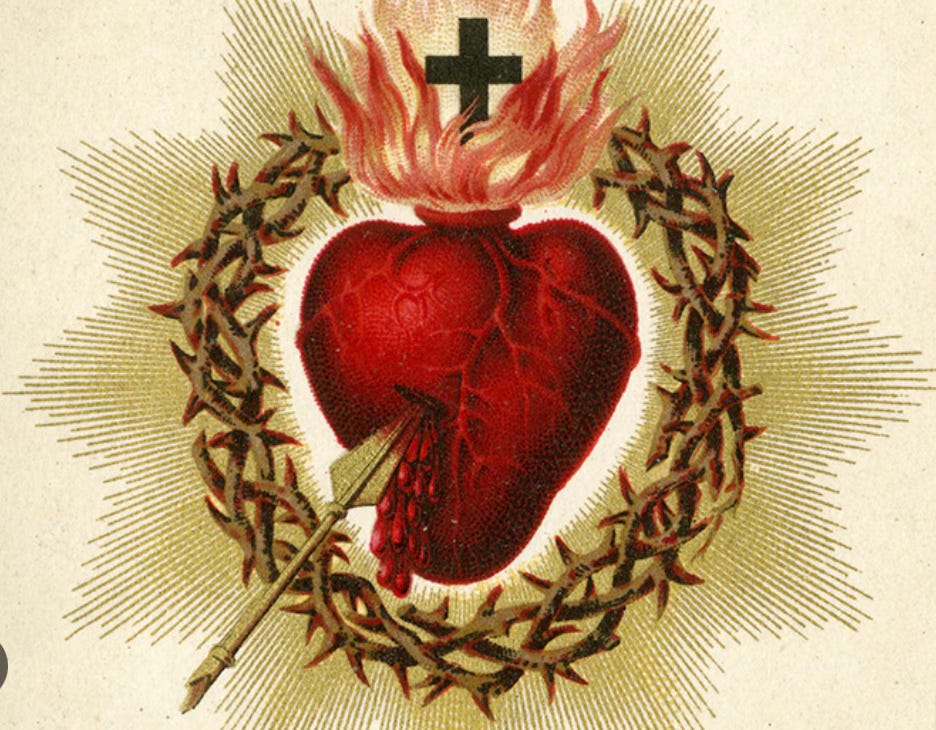

I’m Catholic and spend a lot of time talking to priests. I have cried in confessionals all over the D.C. metropolitan area, and I always learn something when I do. Priests tell me that faith is not a feeling in the same way love is not a feeling, at least not primarily. Faith is habit and ritual embodied by the sacraments, especially the reception of the Eucharist. It’s this ritual and return that constitutes faith, not the feelings I have about God on difficult days.

Sadness is a feeling, and it’s important to acknowledge it. But both faith and love are a choice. Those of us who show up in the pews on Sunday aren’t less battered by life than those posting about hopelessness online. We’re the ones who decide to keep going. All of us have that choice.

This is why those nihilistic memes make me angry. None of us have a right to feel that nothing good will ever happen again. It’s normal to be sad sometimes - life can be brutally unfair. But being miserable all the time is, well, miserable. And in the end, despair drives away the people we love.

I choose to believe that good things will come instead.

Joan Didion, “On Self-Respect,” 1984, https://yale.learningu.org/download/85e1ca3695ab0e000f2c8bf10be1a59d/S574_didion_respect.pdf/.

Id. at 217.

Id. at 218.

I discuss this at length here:

Confronting the Grand Inquisitor

Thank you for reading the following piece! Dostoevsky’s view of Catholicism and my rebuttals could fill a book. I could not address every potential topic here, though I hope to go into great depth about this topic someday.

Jeanette Decelles-Zwerneman, “Fyodor Dostoevsky: A Brief Biography,” Cana Academy, (9 November 2021), https://www.canaacademy.org/blog/fyodor-dostoevsky-a-brief-biography.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, Picador (New York), 2021, Book V, Chapter 4.

Id. at Book II, Chapter 6.

Id. at Book II, Chapter 7.

Id. at Book XI, Chapter 4.

Fr. James Coles, “When Dostoevsky Was Dying,” Scholé, (21 February 2021, 2:42 PM), https://frjamescoles.wordpress.com/2011/02/21/when-dostoevsky-was-dying/.

Loved this! Another Dostoevsky quote that fits the theme:

“Man is fond of reckoning up his troubles, but does not count his joys. If he counted them up as he ought, he would see that every lot has enough happiness provided for it” (Notes From Underground).

In Steinbeck’s Travel’s With Charlie he has a similar idea to Dideon’s - that all the hardships of crossing deserts and brutal mountain terrain are what made the people coming to the fruitful valleys of California worthy of their inheritance. It’s not what he had in mind, but I like to think of sanctification in a similar way. All these trials will give way to glory and are a preparation for our inheritance in Christ.